- Home

- Brennan, Gerald

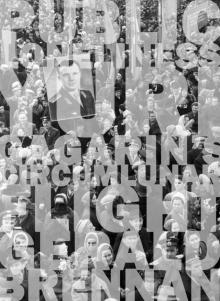

Public Loneliness: Yuri Gagarin's Circumlunar Flight

Public Loneliness: Yuri Gagarin's Circumlunar Flight Read online

PUBLIC LONELINESS

PUBLIC LONELINESS

YURI GAGARIN’S CIRCUMLUNAR FLIGHT

PART OF THE ALTERED SPACE SERIES

GERALD BRENNAN

TORTOISE BOOKS

CHICAGO, IL

FIRST EDITION, JULY, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Gerald D. Brennan III

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Convention

Published in the United States by Tortoise Books. (www.tortoisebooks.com)

ASIN: B00M85XT9O

This book is a work of fiction. All characters, scenes and situations are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

“Meeting of Yuri Gagarin in Vnukovo airport, 1961.” Photo credit ITAR/TASS. Used with permission per license agreement.

“Yuri Gagarin, 1965.” Photo credit ITAR/TASS. Used with permission per license agreement.

Yuri Gagarin statue photograph Copyright © 2014 by Viacheslav Lopatin. Used with permission per standard Shutterstock license agreement.

Lyrics from Vladimir Vysotsky’s “I Have Two Selves In Me” Copyright © 1969 by Vladimir Vysotsky. Courtesy of “Vladimir Vysotsky: The Official Site.” (www.kulichki.com/vv/eng/) Translated by Alec Vagapov.

Cover Artwork Copyright © 2014 by Gerald D. Brennan III

Tortoise Books Logo Copyright ©2012 by Tortoise Books. Original artwork by Rachele O’Hare.

I wake up.

I’m lying on my back in the moon ship.

I am alone in the 7K-L1, stacked atop a Proton rocket at the firing range at Tyura-Tam.

It is finally the day.

I boarded the ship two hours ago. I had to crawl on a board, an actual wooden board, from the gantry through the access point in the launch shroud. (This mission has been planned in such haste that there’s been little time to develop all the little extras, like a proper metal access ramp.) Then I had to drop through the moon ship’s top hatch legs first, holding on to an actual rope rope while the technicians watched warily. Once I got settled and strapped in, we ran through communications checks with the ultra-high frequency antennas, but while monitoring the other systems someone saw a low pressure reading in the liquid oxygen tank on the Block-D stage. They told me to wait while they topped off the tank and monitored the pressure to make sure it wasn’t a leak. And while they were doing that I had nothing to do and so I fell asleep. I was alone in the ship without even a porthole—they’re covered until the shroud is jettisoned after launch—and I fell asleep.

A radio voice in my headset. Academician Mishin: “Cedar, this is Dawn-1.” (The same call signs I had on East-1. The ground stations are always Dawn-1, Dawn-2, etc. And every cosmonaut has a code name. The others chose obvious ones—Falcon, Hawk, Eagle, Golden Eagle. But I am Cedar.)

“Dawn-1, this is Cedar. I am feeling good.” It is at least more comfortable this time; I’m in cloth coveralls, rather than the pressure suit. “I am…well-rested. What is our status?”

“Cedar, it seems to be a faulty sensor. You are on fifteen-minute readiness.”

“Very good, Dawn-1.”

The mission has been prepared in utmost secrecy.

Yes, I went through the normal rituals—the trip to Red Square, to Lenin’s Tomb and the Kremlin Wall—but in the predawn hours, so as not to be seen. Then back here to spend the night in the little white cottage with the metal frame bed and the bare wooden floor. The same place I slept six years and six months ago. The last night before everyone in the world knew my name. The last normal night of my life.

This time it was decided that there would be no whispers or rumors. No helpful hints to journalists that they should be prepared for a major announcement. There was an unmanned circumlunar test of the 7K-L1/Proton combo six weeks ago, but as far as the outside world is concerned, this is just another test. A ship with a mannequin stuffed with radiation sensors broadcasting taped messages. Another Ivan Ivanovich. The decision was made in a late-night meeting of the State Commission after prodding from on high; it was followed up with decrees stamped: DO NOT DISPLAY. DISSEMINATION PER LIST. And the lists have been short.

The announcement will come via television when I am coming around the moon. And of course then it will be too late for anyone to do anything about it. They will broadcast my face from the capsule and live pictures of the moon from my ship and everyone will know that I was first, that a Soviet man was first. And Yuri Levitan will read it out on the radio. And the people will cheer, again.

(Surely that’s the best way to do it. Why announce it ahead of time? At best, everything goes as planned, and where’s the excitement in that? Or perhaps there is a little bit of drama, some unexpected deviation from the plan. And while that gets people interested, it also makes the planners look foolish. But to announce that it is done, that the planners worked in secrecy and executed everything perfectly and now, right now, there is a real man, a Soviet citizen, rounding the moon…surely that’s the best way to do it.)

“Cedar, give us a reading on your environmental systems.” Mishin says. He is on the radio supervising everything, just as Korolev was on that famous morning. With Korolev—Sergei Pavlovich—I had a natural affinity. I was the son he wanted. He was the father I could look up to. Mishin and I have no such relationship. I am the wayward son; he’s the father who worries he isn’t getting enough respect. But it is sometimes convenient to copy the shape of past things, even when the feeling is wrong.

I scan the gauges. “Cabin pressure – 1 atmosphere. Humidity – 60. Temperature – 20 degrees.”

“Very good. 10-minute readiness.”

There were plans to launch the Union instead, in April—to send it on its maiden voyage with Komarov at the helm. Then we would have launched another, so they could rendezvous in space in advance of the May Day celebrations. Certainly we’ve gotten used to being first—the first satellite, the first man in space, the first woman, the first man to walk in space, and so on. And this would have been the first physical docking of two manned spacecraft. A union of Unions! What’s more, we would have had a transfer between the two ships, to send two men back in a different craft than they’d launched in.

But White Tass has been full of black news. The American Gemini program has been a tremendous success. And despite recent setbacks, they’re still on track to go to the moon with Apollo. Such brashness—to say such things in public, then follow through! It’s like playing against a basketball team that diagrams their plays on a chalkboard for all to see, but is so powerful that one ends up falling behind regardless. The only tactic against such an adversary is cunning and guile. You can’t run the same type of plays—that’s the surest path to defeat. Plus, there were glitches with the Union that could not be resolved in time. So Komarov’s mission was cancelled.

It was by no means certain we’d be able to do something better. Sergei Pavlovich’s death last year was a great blow. But Mishin is a competent engineer. Whatever his failings as a leader, we are here, and it is time to do this. Plus, we’re not using Korolev’s boosters this time around. Before Khrushchev’s fall, Chelomey had secured the necessary decrees to develop the Proton rocket strapped to my back, and to initiate development work on a circumlunar flight.

So we have been laying the groundwork for this for some time. And when news came of the Apollo fire—well, certainly it was sad, and humbling. There is a level I hope beyond politics or ideology where we can all mourn such things. For us at Star City—once Kilometer 41, once the Green City—it was particularly sobering

. This was, after all, the first loss of life in a spacecraft—a clear reminder that death haunts this business, that someday we will lose someone during an actual spaceflight. But after the initial pang of emotion, there always comes the calculated thought. And that was: we have some breathing room. They’ve stumbled, and we can pull back ahead.

And so, the decision: to launch the circumlunar flight in October 1967, to coincide with both the 10th anniversary of our first satellite and the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution. A triumph that will call to mind past triumphs, while also surpassing them.

“Five minute readiness, Cedar.”

“Understood. I am feeling well.”

Switches and gauges. Knobs and buttons. The little globe under glass. Everything looks fine. Underneath I feel uncertainty. We have prepared in haste. But everything looks the way it is supposed to look.

“One minute readiness, Cedar.”

This is what I want to hear. I smile, though I don’t know if the camera can see it. “I am ready.”

I have been waiting for this day for two thirds of a decade. Waiting for this moment. There is no countdown for our launches. The final seconds are falling away without a sound.

Then, from Mishin: “Feed one.” Starting telemetry. Graph paper rolling underneath pens drawing peaks and valleys. “Key in launch position. Vent.” The launch commands are enabled. The moon ship is ready. “Feed two.” Backup telemetry.

And at last: “Launch.”

Beneath me pumps are opening. The rocket is waking up. Nitrogen tetroxide and heptyl igniting on contact. Toxic dragon chemicals. Brownish-yellow clouds I cannot see. And fire. (My life has been forged by fire—a childhood in the Great Patriotic War, a youth at the foundry at Lyubertsy, an adulthood perched at the end of various jet engines. Then with East-1, you might say I was born again of fire. And now this.)

I feel a rumble rising through my back, and the hairs on my arm have gone to gooseflesh, and I feel the rocket starting to rise, and over the noise I hear the radio voice: “Liftoff.” And I’m being pressed down into the launch couch, but I find myself shouting: “Here we go again!”

The rocket pushes relentlessly. Soon my chest is tight. But I am mindful of the controllers and I want to reassure them. “I am fine, I am in excellent spirits, the rocket is working perfectly.” I feel like I’m repeating myself from last time. But it is just as well. Radio dialogue is boring. We speak in short sentences and convey only the necessary information. Maybe a few banalities. We can talk at length later. At any rate I’m too excited to be profound.

There is a jolt as the second stage ignites. Then the pyrotechnic bolts fire and the first stage falls away. My eyes scan the mission clock. Just over two minutes have elapsed. I’ve been worried about Chelomey’s rocket, but it is doing everything it’s supposed to do. And Glushko’s engines are working perfectly. So everything is as expected. “Staging complete,” I call out.

It may disappoint you to learn that nobody really flies a rocket into orbit. The gyroscopes and fuel pumps and ignition timers are calibrated to do nearly everything, so we are reduced to monitoring the systems. My fragile life is perched precariously atop a flaming pedestal which at any moment could topple, crush and incinerate me, send my shattered blackened bones falling to the Kazakh steppe. I may have a second or two to avoid that fate by pulling the handle on the escape tower, which will pull my spacecraft free from the presumably exploding booster. So I must keep my eyes on the gauges. Other than reporting on my status, this is my only task: to be prepared. To be, in general, rather than to do.

My body shakes as the rocket rumbles beneath me. But soon there is a pleasant smoothness. Steady acceleration. Less buffeting. The atmosphere is getting thinner.

Then comes a whoosh as the escape tower pulls away. The launch shroud falls off and I can see my first glimpses outside: the arc of clouds and the darkening sky.

•••

Before I continue, I should at least ask: who are you?

In the isolation chamber, before East-1, I prided myself on knowing who I was talking to. They sent me in for two weeks. Two weeks locked behind a giant steel door in front of a one-way mirror, with them keeping an eye on my every move, and me just sitting there in a chair. (Oh, there were tasks—panels and buttons. And meals—squeezable tubes of meat and cheese paste. But it was tremendously boring. Again, just sitting there being.)

Kamanin, the director of our flight training, had orchestrated these intense periods of observation. He was (and of course still is) a general, an accomplished aviator, the very first Hero of the Soviet Union—and an unrepentant Stalinist, with the consequent obsession to keep an eye on people. Public loneliness, the watchers called it. They wanted to watch you without you watching them.

So I was stuck in there, observed and isolated, with little to do but go on about my duties. And I found myself singing—composing odes to my tubes of food, little ditties to keep my spirits up. Yes, singing to my food!

Tubes of glorious socialist cheese!

You empty yourselves to fill us up!

You must have read what Marx once said:

To each according to his need!

New Soviet cheese!

So nourishing to me!

You must have heeded Kamanin’s words:

To Yuri according to his need!

I pretended to be lost in my isolation, but I heard a chuckle—a stifled little transmitted laugh—before they cut the microphone. And it seemed like something that would put me in good standing—just the right mix of political ardor and political humor.

More importantly, I knew I could get away with it, for I knew who was in the control room! I had memorized the names of all the watchers! I had procured a work schedule—never you mind how!—and studied it, hard-wired it into the circuitry of my brain along with all the rocket specifications and capsule diagrams we also had to learn. And I was able to call them out at every shift change, with name and patronymic. Greetings, Ivan Pavlovich! Greetings, Pavel Ivanovich! And—well, it certainly didn’t hurt. In fact, how could they not be impressed? This always gets people’s attention—when they think they have arranged a certain number of outcomes, and they seem to believe they have the power to compel you to pick from among those outcomes, and you instead engineer something else through naked determination.

Which is what I’ve done again, with this moon mission. I’ve clawed my way out of the spotlight and back into the cockpit. I’m a different man: not the perfect Soviet specimen I once was. Thinner hair, thicker waist. A scar on my eyebrow—never mind how it got there. What matters is where I am now. Despite the petty jealousies of nameless adversaries, I’ve made it back to where I wanted to be all along.

I trust you’re happy for me. Do you feel a certain kinship with me, a certain bond? Perhaps you’ve been studying facts of my life, everything you don’t know about Yuri Gagarin: where I was born, where I went to school, and so forth. You might be looking for similarities between yourself and me—a shared birthday, or even just a Zodiac sign, if you believe in that sort of thing. Maybe you’re trying to analyze my name—Yuri, derived from George, like Georgy and Yegor—to see if my birthday is your name-day, or vice versa. You could even be looking at political and religious issues: looking for proof that I’m a committed atheist, or a closet Christian; a good Russian son of the soil, or a secret admirer of the West; a sincere Soviet, or one who quietly questions the regime. Or perhaps you’re just looking at certain traits of mine and telling yourself they’re yours as well: intelligence, courage, determination, humor under pressure.

If so, I can certainly understand it—I’m not trying to criticize you! To be human—there is always that longing for connection. And especially with someone like me, someone who’s done some remarkable thing, there is that hope for something shared. (Unless you’re sure we have nothing in common, in which case you’re perhaps looking to downplay my accomplishments, to find proof that I’m not worthy of the praises I’ve been give

n.) I hope I’m not putting words in your mouth or thoughts in your head! I’m not trying to be rude or make assumptions, just speculate for a bit. You’re perhaps looking for these connections, so that you can see a bit of you in me, and by association, a bit of me in you. It’s quite all right! I’ve done the same thing with my heroes: Heroes of the Soviet Union like Alexey Maresyev, Nikolai Gastello and Alexander Matrosov; pioneers of rocketry like Korolev and Tsiolkovsky; even literary heroes, particularly the various characters from Tolstoy.

I am eager to tell some stories—not just about this flight, but also about my life. (Yes, I’ve already written my autobiography, but there are always certain strictures to be observed in such a setting. And I of course was hoping for another flight, so I had no interest in saying absolutely everything. Is that dishonest? I don’t think so. It’s normal to present the best side of yourself when you’re trying to gain favor. You surely do the same thing when you’re getting to know someone and you don’t quite know if you can trust them—on a date, perhaps, or while trying to secure employment.)

Still, you have me at a disadvantage. You know who I am—everyone does. I’m a real man. A Soviet man, a Russian. But I have no idea whether you are communist or capitalist, atheist or Christian or Moslem or Jew. How can I know what stories to tell if I don’t know who you are?

But perhaps it doesn’t matter. If you’re even remotely curious about what it means to be a real man, surely this story will interest you.

•••

When the Block-D stage finishes I feel a familiar shift in my body against the straps. Again I am weightless. There is no time to get unstrapped—we have less than one orbit to prepare before the Block-D will reignite for the next firing, the big one, the one that will send me moonward. But on that three-day trip there will at least be time to enjoy the feeling at last.

Public Loneliness: Yuri Gagarin's Circumlunar Flight

Public Loneliness: Yuri Gagarin's Circumlunar Flight